|

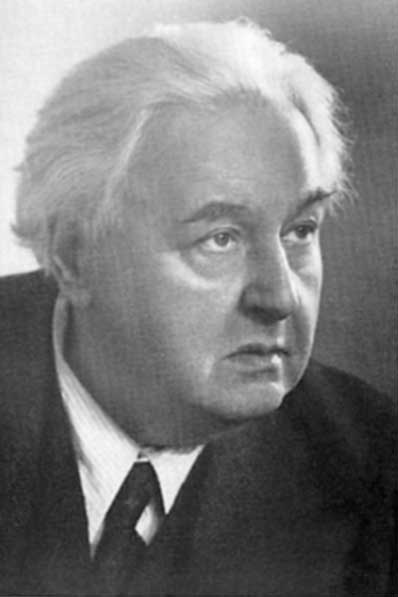

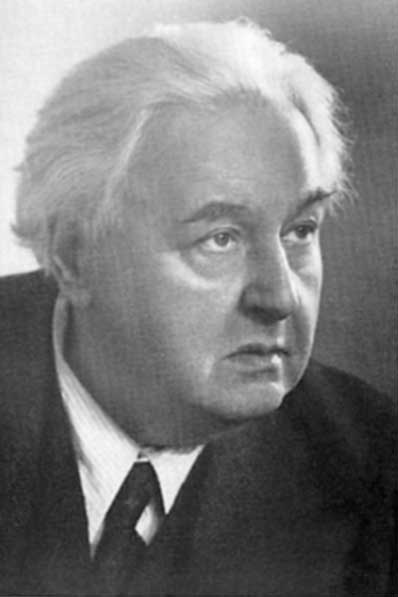

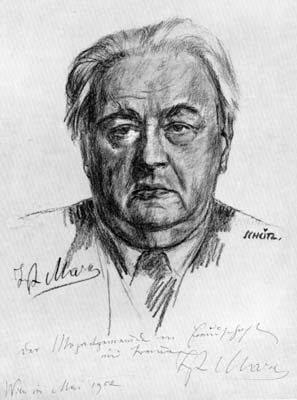

(1882–1964) Impressionismus

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1882–1964) Impressionismus

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Joseph Marx Society has its own website:joseph-marx-society.org

Austria's leading contemporary composersand the author of this website founded theJoseph Marx Society(English translation by Berkant Haydin) On April 1st, 2006, the inaugural meeting of the first Joseph Marx Society in history took place

in Vienna. Berkant Haydin, the author of this website who had registered the society at the Austrian authorities in March, founded the Joseph Marx Society with

Austria's leading composers and music officials: Friedrich Cerha -who has completed and orchestrated Alban Berg's opera "Lulu"- with his wife Gertraud, the celebrated composer

Kurt Schwertsik, the influential Austrian music critic and Marx pupil Peter Vujica, Haide Tenner (President of the Vienna RSO), Eric Marinitsch (Promotion and Marketing Director of Universal Edition),

Heinz Prammer (European Cultural Services) and Robert Hanzlik (a renowned music researcher). Email: Donations account of the Joseph Marx Society in Vienna: Transfers within Austria: |

One of the remaining mysteries of music history is why Joseph Marx, titled "the leading force of Austrian music" by William Furtwaengler in 1952, is no longer counted among the great composers of the 20th century. The Styrian composer received an enormous number of honors and awards over the course of his long life, but he was also held in high esteem as one of the most active music officials, composition teachers and critics of the mid-European late Romantic era. As numerous surviving contemporaries can confirm, he even occupied a key position in the Viennese music scene over several decades. Thus it is not surprising that the Ataturk government called him to Turkey in 1932, where he acted as first advisor on the development of Turkish music and concert life, and where he also helped to build up the Turkish conservatory (later, Hindemith and Bartok stepped in). His surviving students recall that Marx, whose friends were famous contemporaries like Puccini, Szymanowsky and many others, also had extensive knowledge in the areas of literature, art and sciences. His entire student body "adored and admired him like a semi-God". His reputation as Austria's leading musical authority soon spread to all corners of the earth, and young musicians from all over the world made the long journey to Austria, to receive instruction by Marx who had also made a name for himself as the composer of many internationally famous songs. And this is where the origin of the extraordinary career of Joseph Marx lies.

Born in 1882 in Graz as the son of a doctor and a female pianist, Marx was fascinated from an early age with poetry as an art form and also had an intense relationship with nature (throughout his life, he maintained a close affinity with nature). On the musical side, in his younger years he was greatly influenced by Debussy and Scriabin, both of whom he deeply admired. Following the composition of numerous organ and piano pieces and a couple of trio and quartet works that he arranged himself around the turn of the century (to date unpublished but in those days partly performed with great success), Marx concentrated mainly on piano songs which he accompanied himself. He was, incidentally, also a brilliant pianist. Even in the last decade of his life, he was still able to easily perform even the most difficult piano pieces, by heart, and he often demonstrated this skill during his lessons.

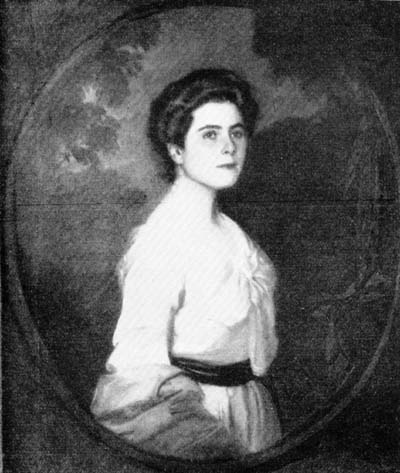

At the age of 25, while performing at a Lieder evening, Marx met the singer Anna Hansa (1877-1967) who stemmed from one of the best families of Graz. Anna Hansa had many contacts to musicians and artists. She had opened a café in Graz that introduced a new concept: It acted as a point of cultural exchange among various artists and also as a locale for musical performance evenings. His initial friendship, and later his life-long love for Anna, changed Joseph Marx's life forever. An established singer, she performed the promising young composer's Lieder and thus helped him to make his final breakthrough as the most-performed song composer of Styria.

Joseph Marx's thinking was initially influenced by the epistemologist Alexius von Meinong (1853-1920) and later also by his friendship with Vittorio Benussi (1878-1927, one of von Meinong's famous students), an experimental psychologist with whom he extensively discussed the psychological mysteries of music. Eventually, he became convinced that tonality was a natural law and, as such, an irrevocably unity with the heart and spirit of man. This has been impressively documented in his literary work "Weltsprache Musik" ("Music - A universal language"). A close friendship with the poet Anton Wildgans (1881-1932) and also his own studies in philosophy, art history, German language/culture and archaeology at Graz University finally rounded off Joseph Marx's education as a highly sophisticated man.

His 1909 dissertation "About the function of intervals, harmony and melody in the comprehension of tone complexes" attracted great attention and by 1912, he had already composed 120 songs, some of which had been very successful in Austria. In 1914, he was offered a professorship of music theory at Vienna University's Music Academy, where he taught from then onward. There, Schreker and other famous contemporaries were among his colleagues. In 1922, he succeeded Ferdinand Löwe as director of the Academy and later became director of the Music College. Following his time as advisor to the Turkish government (1932-33), Joseph Marx became a music critic for the Neues Wiener Journal (New Vienna Journal) in the Thirties and later worked in the same field for the Wiener Zeitung. During his time of teaching in Vienna and at Graz University, he taught a total of 1255 students from all over the world. He did not finish teaching until approximately the mid-fifties, when he had already made history, not only as one of the most important representatives of classical music in Austria, but also as the most influential opponent of the New Viennese School. With his oppositional stance, Marx found himself in good company. Aside from his Austrian fellow-opponents (among them Wilhelm Kienzl, Alois Melichar und Franz Schmidt), he also received active support from abroad. Frederick Delius, for instance, one of England's musical counterparts of Marx, called Schoenberg's progressive style an "atonal ugliness". Yet, among those opponents to the modernists, Marx was certainly - leastwise in the middle European parts - the most conspicious and active one. His sharp wit, applied not only in his function as critic and teacher against the Schoenberg circle but also as jury member in several national and international competitions, never spared any of the young atonal-polytonal composers.

Aside from his early outpouring of Lieder, Joseph Marx wrote several popular choral works (among them the orchestral works "Autumn Chorus for Pan" and "Morning Chant"), as well as some exquisite solo piano and chamber music (among them three string and three piano quartets, two violin sonatas, one piano trio, several works for cello and piano and some chamber pieces with voice). Additionally, he left behind a comprehensive orchestral oeuvre, including the Romantic Piano Concerto, completed in 1919, as well as his major work, the Autumn Symphony (1920/21) which could rather be described as a rhapsody of near gigantic proportion. Further, there is the Nature Trilogy including three stunning symphonic poems, a second piano concerto titled Castelli Romani and many more.

Within the international composers' community, Marx was held in high esteem. For instance, the prolific Russian-Canadian composer Sophie Carmen Eckhardt-Grammaté (1902-74) once said about him that his music had "defined the entire era". Also, no less a man than Nikolaj Medtner (1880-1951), one of the most influential members of Moscow's famous circle of composers in the late 19th Century which included masters such as Sergej Tanejew, Alexander Skrjabin und Sergej Rachmaninov, wrote in a letter to Marx on November 41th, 1949: "My meeting with you was an unexpected gift and also a sign showing that everything that is unexpected, fantastic and ETERNALLY romantic does still exist, despite all the efforts of the contemporary 'leaders' of art who strive to eradicate these values."

In view of such evident verification of his skills, we must ask why this widely renowned composer has been so undeservedly neglected. One of the main reasons might well be the mistaken belief that Marx had been an ultraconservative, even a backward composer - a claim that cannot be substantiated by anyone undertaking the detailed study of Marx's full oeuvre, especially when compared to the composers of his time who were more famous but similar in style. In his capacity as a high-ranking music functionary and critic, and without doubt as a traditionalist and one of the great protectors of tonality, Marx was very prominent and successful in setting the Viennese tone of the time. As such, he has never made a secret of his admiration for the founding fathers of music (Mozart, Schumann, Bach, Haydn etc.). In several of his own works - "Old Vienna Serenades" of 1941, for instance - he used variations of their well-known and lesser-known themes and incorporated motifs of Carl Michael Ziehrer, Joseph Haydn and others. One can also examine his string quartets in modo antico and in modo classico, arranged for string orchestra, where Marx paid homage to his role models in a most impressive manner. With his music, Marx certainly also meant to make available an instructive guideline for young composers, and he succeeded. The classicist works from his final creative period, just like his works stemming from his first outpouring of Lieder, have influenced an entire generation of musicians, as is confirmed by numerous letters to Marx and by other important documents. The great cellist Pablo Casals, for instance, once said that Marx was "absolutely indispensable for maintaining the musical culture of the future", and also that the "non-musique of particular famous contemporaries" was "certain to fail".

It should never be forgotten that the essential purpose of music is not to separate people but to give them pleasure. And this is what Joseph Marx unquestionably intented to do. The vast melodiousness and refined harmonies of his scores mirror the versatile, sparkling essence of this composer. A profound lyricist and yearning optimist, he wants to share his bottomless joy of life with others. Thus, as a poet of happiness, Joseph Marx who died at the age of 82 in 1964, occupies a very special place in music history and as such also deserves a corresponding presence in the world's concert programs.

© Berkant Haydin

Translated from the German by Tess Crebbin

"The genuine work of art is as organic as a

tree developing out of a seed, growing, blooming; its splendour is

natural yet intangible, a thousand fragments joining, and yet of

unimaginable beauty beyond description..." (Joseph Marx)

Joseph Marx's life briefly:

Joseph Rupert Rudolf Marx (sometimes

incorrectly spelled Josef Marx) was born 11 May 1882 in

Graz/Austria. He first studied music with his mother, then was  educated at Johann Buwa's piano school where - among

many others - Hugo Wolf had also been a student. There he was also

taught to play the violin and meanwhile autodidactically learned

the cello too. His first exercises in composition date from his

time at secondary school when he began to arrange pieces for trio

or quartet from existing themes. In the meantime he had also become

a member of the piano school's ensemble as a piano accompanist. His

parents forbade him to play the piano but he found other ways to

realise his love for music. It was at this time that he began to

compose his first piano pieces and to perform them with the

ensemble of his music school. Before having finished secondary

school he planned (or pretended?) to become a watchmaker while he

was thinking of starting an education in photography, but then he

turned back to secondary school and finally finished his studies.

At Graz University he attended courses in philosophy and art

history after having followed for only one year his father's wish

that he should read law. This decision produced a break between him

and his family. Nevertheless, his strong interest in music made him

continue to compose at the age of 26 so that within only four years

(1908-12) he wrote around 120 songs. His name became known in

Vienna, where in 1914 he was offered the post of professor of

theory at the music academy.

educated at Johann Buwa's piano school where - among

many others - Hugo Wolf had also been a student. There he was also

taught to play the violin and meanwhile autodidactically learned

the cello too. His first exercises in composition date from his

time at secondary school when he began to arrange pieces for trio

or quartet from existing themes. In the meantime he had also become

a member of the piano school's ensemble as a piano accompanist. His

parents forbade him to play the piano but he found other ways to

realise his love for music. It was at this time that he began to

compose his first piano pieces and to perform them with the

ensemble of his music school. Before having finished secondary

school he planned (or pretended?) to become a watchmaker while he

was thinking of starting an education in photography, but then he

turned back to secondary school and finally finished his studies.

At Graz University he attended courses in philosophy and art

history after having followed for only one year his father's wish

that he should read law. This decision produced a break between him

and his family. Nevertheless, his strong interest in music made him

continue to compose at the age of 26 so that within only four years

(1908-12) he wrote around 120 songs. His name became known in

Vienna, where in 1914 he was offered the post of professor of

theory at the music academy.

In 1922 he became director of the

academy, and he was rector (1924-27) when the institution was

reorganized as a Hochschule fur Musik. He then acted as adviser to

the Turkish government in laying the foundations of a conservatory

in Ankara (1932-33). From 1931 to 1938 he was music critic for the

Neues Wiener Journal and after World War 2 he worked in the same

capacity for the Wiener Zeitung; during World War 2 Marx was the

most frequently performed composer in Austria which becomes

apparent in the fact that he has later been president, chairman or

honorary member of many important Austrian music associations and

societies over two decades until he died 3 Sept 1964 in Graz at the

age of 82. During his 43 years as a teaching professor in

composition, harmony and counterpoint Marx had 1255 students from

all over the world many of which later achieved national and

worldwide fame as composers, conductors, soloists, musicologists

etc. As Marx enjoyed great popularity and much respect during his

lifetime, there is no question that he had an immense impact on at

least two generations of musicians in the

20th century.

In 1922 he became director of the

academy, and he was rector (1924-27) when the institution was

reorganized as a Hochschule fur Musik. He then acted as adviser to

the Turkish government in laying the foundations of a conservatory

in Ankara (1932-33). From 1931 to 1938 he was music critic for the

Neues Wiener Journal and after World War 2 he worked in the same

capacity for the Wiener Zeitung; during World War 2 Marx was the

most frequently performed composer in Austria which becomes

apparent in the fact that he has later been president, chairman or

honorary member of many important Austrian music associations and

societies over two decades until he died 3 Sept 1964 in Graz at the

age of 82. During his 43 years as a teaching professor in

composition, harmony and counterpoint Marx had 1255 students from

all over the world many of which later achieved national and

worldwide fame as composers, conductors, soloists, musicologists

etc. As Marx enjoyed great popularity and much respect during his

lifetime, there is no question that he had an immense impact on at

least two generations of musicians in the

20th century.

![]()

Click here to view a

more detailed biography that I wrote for a small music publisher

Joseph Marx was a tall and rather strongly

built man. He was considered an excellent pianist who used to

accompany his own compositions on the piano with often quite

demanding piano parts until old age, electrifying critics and

audience alike. His students, acquaintances and colleagues

described him as an out-and-out individualist and, at the same

time, as an open and frank man with a philosophical background and

a subtle sense of humour. He was always described as witty and

eloquent and as someone who knew how to express his thoughts

brilliantly. That is why his lessons were given in a stimulating

and humorous atmosphere where he sometimes told anecdotes about his

encounters with many renowned composers whom he knew or had known

Joseph Marx was a tall and rather strongly

built man. He was considered an excellent pianist who used to

accompany his own compositions on the piano with often quite

demanding piano parts until old age, electrifying critics and

audience alike. His students, acquaintances and colleagues

described him as an out-and-out individualist and, at the same

time, as an open and frank man with a philosophical background and

a subtle sense of humour. He was always described as witty and

eloquent and as someone who knew how to express his thoughts

brilliantly. That is why his lessons were given in a stimulating

and humorous atmosphere where he sometimes told anecdotes about his

encounters with many renowned composers whom he knew or had known

personally (for example Puccini, Szymanowsky, Franz Schmidt). The

course of his lessons was characterized by improvisation: The

students were not allowed to take notes in order to develop

an intuitive over a mechanical understanding and

practical application. He used to further the talents of his

students in an almost imperceptible way and corrected them only if

they committed technical mistakes. It is also known that Marx gave

private lessons to many of his students in need of additional

support, even in his spare time and without demanding any fee.

Despite his very critical attitude towards the atonal avant-garde

he also praised compositions of young modernists provided that they

could be assigned at least to some extent to tonal music. He was

respected by students and colleagues alike, even by those

advocating a very different musical style. In this context it may

be noted that many of his students coming from different parts of

the globe later achieved national and worldwide fame in their

respective musical line. The fact that the total estate of letters

to Marx consisted of 14589 pieces from 3420 correspondents (!),

including a host of well-known persons, should be a clear

indication of the popularity and the renown of Joseph Marx who due

to several unfortunate circumstances fell into oblivion after his

death.

personally (for example Puccini, Szymanowsky, Franz Schmidt). The

course of his lessons was characterized by improvisation: The

students were not allowed to take notes in order to develop

an intuitive over a mechanical understanding and

practical application. He used to further the talents of his

students in an almost imperceptible way and corrected them only if

they committed technical mistakes. It is also known that Marx gave

private lessons to many of his students in need of additional

support, even in his spare time and without demanding any fee.

Despite his very critical attitude towards the atonal avant-garde

he also praised compositions of young modernists provided that they

could be assigned at least to some extent to tonal music. He was

respected by students and colleagues alike, even by those

advocating a very different musical style. In this context it may

be noted that many of his students coming from different parts of

the globe later achieved national and worldwide fame in their

respective musical line. The fact that the total estate of letters

to Marx consisted of 14589 pieces from 3420 correspondents (!),

including a host of well-known persons, should be a clear

indication of the popularity and the renown of Joseph Marx who due

to several unfortunate circumstances fell into oblivion after his

death.

Compositional style

The unique "Marx sound" reminds the listener of

Debussy, Scriabin, Delius, Ravel,

Respighi, J. Jongen, Vladigerov, Reger, Schreker,

R. Strauss, Korngold, Brahms, Mahler and Bruckner but

is in the end totally his own. Regarding his Lieder for which he

became famous (these were mainly composed before he was 30 years of

age) he is said to be the rightful successor to Hugo Wolf.

The southern atmosphere in many of his works has its origin from

his mother who was half Italian half Slav. Marx was a late

romantic impressionist whose musical inspiration was nourished

by his deep and spiritual tie to Mother Nature to whom he

wrote so many glorious hymns of love. This is why the mood

of his music is so sensuous, optimistic and even hedonistic, a work

of art created by a happy man who wants to share his delight with

others.

The unique "Marx sound" reminds the listener of

Debussy, Scriabin, Delius, Ravel,

Respighi, J. Jongen, Vladigerov, Reger, Schreker,

R. Strauss, Korngold, Brahms, Mahler and Bruckner but

is in the end totally his own. Regarding his Lieder for which he

became famous (these were mainly composed before he was 30 years of

age) he is said to be the rightful successor to Hugo Wolf.

The southern atmosphere in many of his works has its origin from

his mother who was half Italian half Slav. Marx was a late

romantic impressionist whose musical inspiration was nourished

by his deep and spiritual tie to Mother Nature to whom he

wrote so many glorious hymns of love. This is why the mood

of his music is so sensuous, optimistic and even hedonistic, a work

of art created by a happy man who wants to share his delight with

others.

The following photographs were shot by Martin

Rucker on April 1, 2003.

"In this house lived the composer Joseph Marx

from 1915 to 1964.

Dedicated by the Mozartgemeinde (Mozart Society), Vienna 1965."

Many more photos of places in Austria where Marx lived and worked can be found here... |

|---|

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT MARX'S FATE AS ONE OF THE MOST UNDERRATED MASTERS OF TWENTIETH CENTURY'S MUSIC READ THE FOLLOWING CHAPTERS.

In February 2000 I came across a CD that was part of Hyperion's "The Romantic Piano Concerto" series (Vol. 18, Hyperion CDA66990). It included two piano concertos by Joseph Marx (Josef Marx) and Erich Wolfgang Korngold one of which impressed me in a way that no music had managed before: The Romantisches Klavierkonzert (Romantic Piano Concerto) by Joseph Marx. After having heard this gorgeous late romantic concerto I began to search for recordings of other orchestral works by Marx but when I began to browse through the existing commercial offerings of Marx works I was truly disappointed since the above mentioned piano concerto was the ONLY orchestral work by Marx available at all. There are a number of recordings of his songs with piano, these appear in the Etcetera and FY Solstice labels. The CD booklet of the Hyperion CD written by Brendan Carroll briefly gave some highly interesting information on a number of Marx's orchestral works but these also were unavailable on the international market. Hence, I gave up searching.

Some weeks later, a good friend from England (a collector) sent me a tape cassette with a recording of Marx's 2nd piano concerto Castelli Romani for Piano and Orchestra that he had received from someone who had taped a German radio broadcast. This recording now ranks as one of the Top 5 of my entire piano concerto collection that currently includes more than 1,500 works. The "Castelli Romani" definitely is an outstanding work of impressionistic romanticism and dazzling beauty. Several audio samples of this brilliant 2nd piano concerto, but also of many other unknown orchestral Marx works are available at this website.

After having heard the "Castelli Romani", I decided to locate recordings of all other orchestral works by Marx. In the meantime, ASV Records, Pavane Records and FY Solstice released CDs with a part of the Marx chamber works (it seems that Marx's few other chamber works might be issued soon). But regarding his orchestral works - especially his Herbstsymphonie that is mentioned in the booklets of all available Marx CDs - I was still groping in the dark...

Brendan Carroll wrote that the most important orchestral works of Joseph Marx (Josef Marx) have never been recorded (liner notes of Hyperion CDA66990). Indeed, only a handful of radio broadcasts have been made in the last 70 years as I know from my own research. Michel Fleury who wrote the booklet articles for the few other commercial Marx CDs also seems to know these deplorable facts. Nevertheless, I had the feeling that there might somewhere exist recordings of Marx's orchestral works and especially of the Herbstsymphonie. I was somehow sure that if recordings did exist I would find them.

First I began to search the World Wide Web but I

failed since there is almost no useful information about Marx's

orchestral works in the whole Internet! Could it really be possible

that none of Marx's orchestral works apart from the Romantic Piano

Concerto had ever been recorded? In order to get an answer I

decided to call the Austrian Radio Station ORF in Vienna. This

turned out to be a good decision since the ORF (who has different

state studios of which all have their own archive) indeed had

recordings of a major part of Marx's orchestral and chamber works.

I was overwhelmed by the list of works  that was read out to me from the archive database. I ordered

all recordings of every work for chamber and orchestral ensemble

that the Viennese radio station had in its archive. Then I asked

the key question: "Could you please check your archive for a work

named Herbstsymphonie (or Herbstsinfonie / Herbst-Sinfonie /

Herbst-Symphonie as it is sometimes spelled)?". I was so excited

and highly expectant. Then the voice at the other end of the line

said "No, I can't find anything like that". This was truly

disappointing to me but at the same time I had the idea to call the

ORF state studio in Marx's hometown Graz which could well have had

a recording. My phone call to the ORF archive in Graz indicated

that they also had no recording of the Herbstsymphonie. At least I

was able to order a few other orchestral and chamber works that the

Viennese archive didn't have. The other ORF studios had nothing

else of interest.

that was read out to me from the archive database. I ordered

all recordings of every work for chamber and orchestral ensemble

that the Viennese radio station had in its archive. Then I asked

the key question: "Could you please check your archive for a work

named Herbstsymphonie (or Herbstsinfonie / Herbst-Sinfonie /

Herbst-Symphonie as it is sometimes spelled)?". I was so excited

and highly expectant. Then the voice at the other end of the line

said "No, I can't find anything like that". This was truly

disappointing to me but at the same time I had the idea to call the

ORF state studio in Marx's hometown Graz which could well have had

a recording. My phone call to the ORF archive in Graz indicated

that they also had no recording of the Herbstsymphonie. At least I

was able to order a few other orchestral and chamber works that the

Viennese archive didn't have. The other ORF studios had nothing

else of interest.

However, this was the beginning of the most extensive phone call campaign that I had ever made in my life.

I called a very large number of eligible

archives, universities, music societies, orchestras, musicologists,

conductors, historians, discographers, lexicographers, pianists and

besides many other persons who are familiar with

the Austrian music

scene, but I also spoke to some of Marx's living pupils and friends

or to their descendants, among these the grand-daughter of the

famous singer Anna Hansa (1877-1967) who has been Marx's lifetime

romance and partner over five decades and to whom Marx had

dedicated his Herbstsymphonie. (Marx himself never had any

children and there are no other direct relatives.) Unfortunately

none of them could provide a recording of the Herbstsymphonie; for

the most part they had never even heard the name of this work!

the Austrian music

scene, but I also spoke to some of Marx's living pupils and friends

or to their descendants, among these the grand-daughter of the

famous singer Anna Hansa (1877-1967) who has been Marx's lifetime

romance and partner over five decades and to whom Marx had

dedicated his Herbstsymphonie. (Marx himself never had any

children and there are no other direct relatives.) Unfortunately

none of them could provide a recording of the Herbstsymphonie; for

the most part they had never even heard the name of this work!

Anna Hansa

I contacted the Universal Edition, the main publisher of Marx's scores. Of course they also had no recording of any of Marx's orchestral works. Now I understood that calling the ORF studios had been the very best idea that I could have had. Nonetheless I asked the Universal Edition if the score of the Herbstsymphonie has ever been loaned. They just saw a curious entry in their database and gave me the phone number of the famous German publisher Schott in Mainz who then gave me the information that the score had obviously been loaned out in 1990 but this turned out to be nothing but a wrong entry in the computer as I discovered several phone calls later - one of which was with a German classical music producer in Mombasa/Kenya!

After that I called the Austrian National Library in Vienna. Their music division had indeed two other orchestral works that even the ORF did not have - of course I ordered them. In the meantime I had been hearing the first batch of recordings from Austria and was deeply impressed: How could such great music be that unknown and totally forgotten? How could a composer who obviously was one of the most approachable composers of the 20th century be that neglected? And what is more, how could his Herbstsymphonie that is Marx's major work due to all sources to which I had access later, be the most forgotten work among his orchestral masterpieces?

Joseph Marx at his home in Vienna, Traungasse 6

(1963).

For more photos of this house please click here

I was hoping to get answers to these questions by reading all the biographies and writings about Joseph Marx that were mentioned in other books and in the Internet (which was rather problematic since his name is sometimes incorrectly spelled Josef Marx). The first book that I received was a doctoral thesis about Joseph Marx written by Dr. Andreas Holzer from Vienna University. This dissertation is the latest and by all means the most comprehensive writing about Joseph Marx. Of course it can't be compared with Andreas Liess's biography since Liess was one of Marx's friends and pupils but it is still the most extensive information source compiled by a person who was not part of Marx's circle of acquaintances as the writers of all other biographies had been.

In Dr. Holzer's thesis I eventually seemed to have found the reason why the Herbstsymphonie had disappeared from the concert programs.

The premiere was performed 5 Feb 1922 by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Felix von Weingartner, as part of the "Philharmonic Concerts" series. The dress rehearsal was disturbed by a circle of saboteurs who used whistles and evidently didn't want the symphony to be successfully performed, and the same happened at the premiere. This divided the audience into three groups: those who loudly whistled in order to disturb the performance, those who were overwhelmed by the euphony of the music and cheered and applauded in order to express their enthusiasm and to drown out the troublemakers, and the rest who just tried to be able to hear the music. Visitors even reported acts of physical violence between the two factions of the audience during a tumult that lasted about fifteen minutes. Unfortunately even Marx himself didn't know exactly which circles were responsible for all that trouble as he wrote in one of his private letters.

Several articles in newspapers and music magazines described the symphony as a work that naturally had to tear the audience apart:

"A masterly thematic and polyphonic work that

sometimes makes use of Schreker techniques ..."

("Musikblätter des Anbruchs", 1923/5, p. 156)

"... an extremely large, even monstrous work

with sometimes excessive sonority and polyphony ... masterly use of

techniques ..."

("Wiener Morgenzeitung", 7 Feb 1922)

"... an unsymphonic symphony ... A too

monstrous work of a lyricist who is wrapped up in his music

..."

("Wiener Zeitung", 5 June 1923)

In spite of the huge attention that the work had attracted in Vienna, its Viennese premiere must be evaluated as a flop. However, there are hints showing that Felix von Weingartner seemed not to be the "right one" to conduct the work as the premiere in Graz (26 Sep 1922) conducted by Clemens Krauss gave a totally different impression of the music so that the symphony was celebrated as perhaps no other symphonic work had ever been celebrated there before. One should note that this was not only influenced by the fact that Graz is Marx's hometown since all later Viennese performances of the Herbstsymphonie conducted by Clemens Krauss were greatly successful and the scandalous premiere of 1922 seemed to have been forgotten.

One additional note: In 1927 the Herbstsymphonie was not performed completely anymore. Marx had meantime decided that the fourth movement ("Ein Herbstpoem"; original title: "Ernte und Einkehr") should be performed as an independent work. This movement is the only one of the four movements that begins after a break while the first three movements of the symphony must be performed without a break.

But why have Marx's other orchestral works also been neglected and forgotten in the following years? One can say that the Austrian music scene of the 1920s was generally divided into two factions: the tonal and the atonal music. Marx was one of the leading members of the tonal group, perhaps even the leading light of the Viennese music scene of that era as one can see from the numerous functions that he had in Vienna. Naturally there were a lot of Marx opponents among other music circles. After Marx's orchestral works had been quite frequently performed in the 1920s the interest in this kind of innovative but still tonal late romantic style began to wane. Seemingly as a reaction to this development, Marx then wrote his three famous string quartets of which the titles ("modo antico", "modo classico") tell much about his attitude towards the modernists.

As my search for a recording of the Herbstsymphonie went on I found a website where the names of all persons who had written letters to Marx are listed. This list was the reason for at least 50 additional phone calls, among which I also called Deutsche Grammophon, the most important German music archives and a couple of German discography experts. None of these could help me with locating a recording. Then I seemed to have found what I was searching for: A document of the Austrian National Library that gave short summaries of each letter written to Marx by Swiss composer and Marx pupil and friend Richard Flury. Here I found a letter in which Flury reported to Marx about the positive reactions to the performance of the symphony in his hometown in Switzerland. Was this a hint or even a proof for an existing recording in Switzerland? Couldn't it be possible that the symphony would have been performed in Switzerland in later years when recordings were frequently and usually made?

Joseph Marx - Richard Flury

I contacted several Swiss radio stations and finally the Swiss National Library that could give me the phone number of Richard Flury's son Urs Joseph Flury who also is a composing conductor and violinist. Urs Joseph Flury knew many things that I hadn't heard of so far since he had all original letters written between his father and Marx over five decades. He also had been searching for a recording of the Herbstsymphonie over a long time but at the end he had given up. Urs Joseph Flury insisted that the summary of that letter at the website of the Austrian National Library was definitely wrong. Finally he read the original letter to me, and indeed we found out that the information about the performance of the symphony refers not to the Herbstsymphonie but to a symphony composed by Flury himself. Urs Joseph Flury said that if a Swiss recording of the Herbstsymphony did exist at all he would know it.

Another important straw was a hint that I found in the Liess biography: The Herbstsymphonie had been performed in February 1925 in Germany by the well known Wuppertal Symphony Orchestra conducted by the Austrian Hermann von Schmeidel.

If you wish to see a photo of recording sessions of some of Marx's orchestral works in the above-mentioned concert hall "Stadthalle Wuppertal" that is exactly the location where the Herbstsymphonie was performed for the last time in 1925, please click here!

After I had contacted the organist and pianist Prof. Joachim Dorfmüller who is an expert on Wuppertal's music and concert history I knew what I had suspected before: The symphony hadn't been recorded when it was performed in 1925. This was confirmed by the German discographers and lexicographers who hadn't found anything about a recording of a Marx symphony in Germany.

It was then, after more than 200 phone calls and reading all the writings about Marx, that I definitely knew that I wouldn't find any recording of the Herbstsymphonie. Nevertheless, I can now claim that this work is by all accounts Marx's most striking work although most likely no living person has ever heard a second of it. The main biographer, Austrian musicologist Andreas Liess, emphasised that it is "among the most polyphonic works ever written", and he almost went into raptures when describing all the outstanding details of the score: "A late romantic symphony of incredibly orgiastic euphony and voluptuous impressionism...". These quotes are taken directly from the detailed description of the score that we can find in his biography written in 1943. These facts might be another reason why the symphony was never performed again since the late 1920s. Only a few conductors and orchestras were willing to tackle such a big challenge. An excellent performance of this work would most probably need extensive rehearsal and above all an orchestra and conductor who really have a special liking for this kind of large scale late romantic symphony. Furthermore, as far as I can say after having seen the conductor's score that runs to 281 pages, it should be performed with much sensitivity and not rushed.

"An ecstatic ocean of themes and motifs, polyphonic turnings, richness and variety." (Erik Werba)

"Why should a composer with such graphic abilities make use of a small instrumentation in order to describe the richness of the autumn? Which delightfully suggestive images of nature are being created by this gigantic orchestra! No matter whether this is indeed a symphony or a magnificent rhapsody..." (Hans von Dettelbach)

"Eine Herbstsymphonie" (Autumn Symphony)by Joseph MarxOctober 24 and 25, 2005 in Stefaniensaal/Graz"recreation" - Großes Orchester Graz (Large Orchestra of Graz)conducted by Michel SwierczewskiA REPORT BY BERKANT HAYDINAuthor and editor of www.joseph-marx.org(Translated from the German by Alan Howe)

How the project came aboutIn 2004 Michel Swierczewski, the conductor of ‘Recreation - Großes Orchester Graz’ (‘Large Orchestra of Graz’), who at that point knew and greatly admired the 1st Violin Sonata by Joseph Marx, set off in search of a special rarity which would be worthy of rediscovery. Thus he had the score of the Herbstsymphonie sent to him by Universal Edition. The 280-page, giant-sized score was subsequently examined by him and a series of orchestral musicians - with great reverence, they told me. When it eventually became clear to everyone that they were dealing with a very extraordinary, mammoth work, they discussed the matter with Mathis Huber, the manager of the ‘Recreation’ orchestra and the 'Styriarte' organisation. Because this great composition of Joseph Marx, himself a native of Graz, had not been heard for about 80 years, Mathis Huber eventually gave the green light for a performance in the autumn of 2005. www.micmacmusic.com

A symphony of superlatives with a complex structureBefore one says a single word about the musical and compositional qualities of the Herbstsymphonie and about the technical quality of the performance by the ‘Recreation’ Orchestra and its conductor Michel Swierczewski, one must - even as experienced critics - understand that it is impossible even for the practised ear to fathom and grasp the Herbstsymphonie in its entirety on first hearing, for it is too sophisticated in structure and at the same time too rich in sound, too polyphonic and too gigantic. For this reason a live performance of the Herbstsymphonie would almost certainly represent a great challenge to any orchestra in the world. Stylistic relationship with great contemporariesIn order to gain a rough impression of the Herbstsymphonie, we should imagine the operas and richly orchestrated works of Schreker, Strauss and Korngold, as well as the symphonies of Bax, Howard Hanson and Vaughan Williams, also the most dazzling passages from works such as "La Mer", "Daphnis and Chloé", "The Poem of Ecstasy", "Prometheus - Poem of Fire" and "The Firebird"; then finally we should mix all this with Marx’s own musical language and set it - in the manner typical of the composer - in a many-layered, logical and carefully designed structure. And so it must be evident that we are speaking here of a bewitching, sumptuous work of gigantic dimensions. Masterly performed by conductor and orchestraOn both of the evenings, along with around one thousand people on each occasion, I was privileged to experience the lavishly scored 75-minute Herbstsymphonie played by an almost 100-strong orchestra under a conductor who combined ecstasy with absolute concentration and exemplary dedication. Even the most difficult, sometimes almost impossible passages in which the entire orchestra and percussion have technically to surpass themselves were mastered with great bravura. Yet the quieter, emotionally contemplative pages were also interpreted so expressively by the orchestra that significant numbers of the audience in the Stefaniensaal were quite obviously deeply moved. In the rows all around one could see many individuals sitting with eyes closed, smiling peacefully and allowing themselves to be swept along by the torrent of ecstatic music. Many must have realised that they had been witnessing a very special musical event. A gigantic flood of soundThe sound world conjured up by Joseph Marx in his Herbstsymphonie - one which, with its countless majestic climaxes and examples of opulent symphonic development, is more like some breathtaking, awe-inspiring roller coaster ride through the Himalayas - plunged the Stefaniensaal into an almost unreal atmosphere. And so perhaps this is why the symphony is so difficult to fathom: even after several hearings of the entire work (the final rehearsal and the two performances of 24th and 25th October), it was virtually impossible for myself and those with me (all of us with long experience of listening to the lushly orchestrated large-scale works of the late romantic period) really to take in what was flooding, indeed shaking our very senses, so stunned were we by the great waves of sound. I would describe it like this: the Herbstsymphonie is so astounding in its power, intensity and lavishness, so brimming with passion, and is as a result in the truest sense of the word so overwhelming that, faced with this wild roller coaster of emotions, anyone who hears it must soon acknowledge his inability to come to an immediate understanding of the piece. And the impression which might arise at this point that the Herbstsymphonie is without structure and thus, despite all its beauties, of little consequence turns out, on a third or fourth hearing - to be a great mistake: The score, woven around just four main themes, contains in fact a clear sense of progression and tension which, in the course of the individual movements that describe autumn in all its phases and emotions, is built logically and stretches from the first to the last minute of the symphony. Furthermore, the many completely unexpected changes of key, harmonic turns and switches between minor and major are evidence of the composer’s unprecedented boldness and almost frightening powers of creativity - which took me, a Marx expert, entirely by surprise. The journey does not end hereThus, from a compositional as well as sonic and psychological point of view, the Herbstsymphonie turns out to be a most extraordinary phenomenon - one which I have never before encountered in such an unrestrained form in all my years of studying the large-scale late-romantic/impressionist works of many other composers. And therefore I find myself unable to describe in simple words the feelings which came over me during the two performances (of which the second of 25th October has remained in my memory as the “better one"). Deep emotions, set off by the virtually unending tone-painting and returning motifs which are hidden everywhere in the score alternated with thoughts and memories of the outset of my research into Joseph Marx which had begun five years ago with - and it must have been fate - my “quest of the Herbstsymphonie”. For me things had to some extent come full circle: the initial objective of being able to hear the Herbstsymphonie sometime in my life and to see it recognised by the public has now been achieved, and it seems to me at this point in time virtually impossible to find something else in the sphere of music which will satisfy my thirst for absolute perfection in sound better than the Herbstsymphonie. So the question that arises is this: what will be next and how shall I proceed? What direction will this musical journey take now? Standing at this turning-point, I direct my attention to the choral works of Joseph Marx which were written years before the Herbstsymphonie and are the only orchestral works by the composer still awaiting rediscovery. A personal thank youAfter all this - and on behalf of the several thousand Marx fans from all over the world of whose existence I am aware - I would now like to offer my most sincere thanks and admiration to the courageous manager of the Large Orchestra of Graz and the Styriarte organisation, Mr Mathis Huber, and also to the fascinating and incredibly versatile conductor Michel Swieczewski, and to all of the esteemed members of the orchestra. I wish the orchestra and its management many further successes in the future and hope accordingly that the orchestral and choral works of Joseph Marx will be performed not only in the place of his birth, but also elsewhere in Austria, as well as in many other countries. HOW THE GRAZ PERFORMANCES OF THE HERBSTSYMPHONIE WERE RECEIVEDVoices from the audience: |

|

For latest news on recording projects and concerts see: |

Note: Some of these choral works are also available in other arrangements.

Joseph Marx (sometimes incorrectly spelled Josef Marx) has been an

active composer over a time scale of almost 50 years. During the first third of this

period he composed a major part of his 150 Lieder (works for voice and piano)

for which he gained worldwide success. Many of his songs were also

published in different other versions (with chamber ensemble/orchestra).

In an interview (1952) Marx said that he -and

also Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss- actually wrote Lieder because

it was the fashionable thing to do. (see interviews in

the section "Audio Samples..."). Despite his image as a "song composer", his true

mastery and achievement is reflected in his works with orchestra

most of which he wrote between 1919 and 1932. By composing these

stunning orchestral compositions Marx finally brought to a

quintessential summation all the complex symphonic ideas that he

hadn't been able to express in his early works.

Joseph Marx (sometimes incorrectly spelled Josef Marx) has been an

active composer over a time scale of almost 50 years. During the first third of this

period he composed a major part of his 150 Lieder (works for voice and piano)

for which he gained worldwide success. Many of his songs were also

published in different other versions (with chamber ensemble/orchestra).

In an interview (1952) Marx said that he -and

also Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss- actually wrote Lieder because

it was the fashionable thing to do. (see interviews in

the section "Audio Samples..."). Despite his image as a "song composer", his true

mastery and achievement is reflected in his works with orchestra

most of which he wrote between 1919 and 1932. By composing these

stunning orchestral compositions Marx finally brought to a

quintessential summation all the complex symphonic ideas that he

hadn't been able to express in his early works.

Most of the details below are the result of extensive investigations that took several months. As I have reported, only a handful of these works have ever been commercially recorded. This opus list was very difficult to compile since all existing lists that can be found in Marx biographies or music dictionaries are incomplete. After having evaluated almost every source that one can have access to, I am now able to present the first and only complete list of all works by Joseph Marx. (Please note that Marx didn't use opus numbers).

An excellent and complete German overview of Marx's works that was

perfectly made by Johannes Hanstein and that is based on my below work list, can be found here.

Orchestral works without voice/chorus:

1916-19:

1st piano concerto "Romantisches Klavierkonzert" (Romantic Piano Concerto) in E major, 37-43 minutes. This amazingly euphonic and extremely virtuosic work has been performed many times by Angelo Kessissoglu (who also performed its premiere), then frequently by the great Walter Gieseking and later in the 1970s and 80s by Jorge Bolet (who reported that he had discovered the score of his "favorite concerto" in the private music library of a friend), and it was eventually issued on a Hyperion CD (CDA66990) with super-virtuoso Marc-André Hamelin. The movements are:

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE 6018). A version for two pianos is also available.

The Austrian pianist Prof. Hans Petermandl who has performed Marx's 2nd piano concerto "Castelli Romani" twice (in 1978 with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Karl Etti and in 1981 with the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Lior Shambadal) told me that one of his pianist friends met Jorge Bolet who could not help saying: "The Romantic Piano Concerto is my favorite concerto. It is so beautiful, so wonderful, you should play it!"

Detailed information on the Romantic Piano Concerto is available here!

1920/21:

Eine Herbstsymphonie (An Autumn Symphony) in B for large orchestra

Dedicated to Mrs. Anna Hansa, famous singer and Marx's Lied performer in the 1910s and 1920s and Marx's lifetime romance and partner from around 1910 until his death in 1964.

Marx began to compose his symphony in 1920 (just after having completed the Romantic Piano Concerto) and finished it 21 Nov 1921. He wrote it in a secluded countryhouse named "Villa Grambach" (Grambach is the name of a small village to the south of Graz). This house owned by Anna Hansa's family was the place where Marx preferably spent the summer months and composed a major part of his music.

Villa Grambach near Graz - The place where Marx composed a

major part of his works and spent much time with his friends Franz

Schmidt, Franz Schreker, Leopold Godowsky, Wilhelm Kienzl, Karl

Böhm, Rudolf Hans Bartsch, Clemens Krauss, Anton Wildgans,

Angelo Kessisoglu and many more. The guestbook of Villa Grambach

shows the names of many composers and conductors of worldwide

fame. If you want to view a couple of great photos of this house

as it is looking today, please click here to see my Travelogue

The available information sources about the duration of the symphony vary between "75 minutes" (Universal Edition's catalogue) and "more than two hours" (newspaper articles from the 1920s). Due to the score of the symphony and the duration of "Feste im Herbst" (see "Latest news"), I would estimate that the symphony should last about 80-90 minutes if performed not rushed.

Orchestration: more than 30 wind instruments, percussion, celesta, two harps, piano and large string orchestra. The movements are:

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE 7438 and 7439)

LATEST NEWS

After 1927 the final movement of the symphony ("Herbstpoem") was performed separately only one last time on 22 Oct 1934 by conductor Bernhard Paumgartner in Vienna (orchestra unknown, likely Vienna SO). This is the very last performance date of any unrevised part of the Herbstsymphonie that I could find at all. Austrian newspaper articles from the 1960s that were sent me by Marx pupil and expert Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Suppan say that the "Herbstsymphonie was re-performed in the 1950s under the title Feste im Herbst" (aka "Herbstfeier", Autumnal Revelries, published in 1946). This is not correct since I found out by chance (in other words: by receiving the inspiration to compare the score of Herbstpoem with my recording of Feste im Herbst!) that the masterwork "Feste im Herbst" that was performed many times in Austria till the 1980s but never commercially recorded is nothing but a shortened and slightly revised re-issue of the Herbstsymphonie's final movement "Herbstpoem"!

What is the difference between "Feste im Herbst" and "Herbstpoem"?

The score of Feste im Herbst runs to 100 pages while the score of the Herbstpoem includes 115 pages. Feste im Herbst is lighter orchestrated (less wind instruments, less strings, only one harp instead of two) and it includes several rhythmical and instrumental changes compared with the Herbstpoem. But aside from this, Feste im Herbst is mainly identical with the final movement of the symphony.

Hard to believe that no-one ever knew that the outstanding work "Feste im Herbst" is a slightly revised version of the final movement of the Herbstsymphonie. Ironically, the first three movements of the Herbstsymphonie that evidently contain a large amount of the composer's theme material of the earlier works (in 1921 Marx had already composed 120-150 Lieder and most of his chamber music) were never heard again since the 1920s.

Marx who has educated more than a whole generation of composers, conductors and musicologists from all over the world during his 43 (!) years as a teaching professor in composition, harmony and counterpoint (he had 1255 students during this long period) most likely has never been happy about the fact that just his largest and most important work has never been performed completely again (let alone recorded) in his lifetime. Hence, the world of classical music clearly needs a complete recording of the Herbstsymphonie.

"Though derived from the last movement of the Autumn Symphony of 1921 "Feste im Herbst" is best regarded as a symphonic poem in its own right. As such it must serve as an appetizer for the much longer parent work from which it is extracted. Hearing this work leads to tantalizing conjecture about how many of the themes, so fleetingly heard in the first part of the symphonic poem, might have been developed at length in the first three movements of the symphony. "Feste im Herbst", in its 1946 revision, marks both the high water mark of German Romanticism and its ebbing in the face of more modern and less lyrical developments. It is a vast confluence of multiple influences, from the Brahms of the second symphony and the Bruckner of the fourth, through Slavonic, even Dvorak-like, dance measures to the impressionism of Debussy. All these are welded together with a Latin lucidity that recalls Respighi. It is the genius of Marx that he weaves these desperate threads together into a design that is in the end totally his own. A great sonorous culmination of the romantic, the very Autumn of the genre. After this there could only come the bleak winter of atonalism and intellectualism. Yet it is a joyous farewell, a rich and glowing sunset that turns the leaves to gold as they fall." (John Rowland Carter)

Joseph Marx in 1925, during the great success of his Autumn

Symphony

1922-25

In this period Marx wrote three breathtakingly impressionistic works that are also known as "Naturtrilogie", "Natur-Trilogie" or "Natur-Suite" (Nature Trilogy or Nature Suite):

Detailed information on the Idyll is available here!

NEWS: A truly gorgeous recording of this "Nature Trilogy" has been released on ASV! For more information on Vol. 1 of the "Complete Orchestral Music" series please click here.

1928:

Festliche Fanfarenmusik (Festive Fanfare Music) in B major for 22 brass instruments and small percussion set. About 4-5 minutes.

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE 18731)

1929:

Nordlands-Rhapsodie (Nordic Rhapsody). About 30-35 minutes. Based on Pierre Loti's novel "An Iceland Fisherman" (1886) about an Icelandic love tragedy, and that's how this remarkable work sounds like. The movements are:

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE 11598)

1929-30:

2nd piano concerto "Castelli Romani" in E flat major: Three pieces for piano and orchestra. 30-35 minutes. Marx had always been inspired by the beautiful landscapes and monuments of Italy since he had been travelling to Italy many times as a child (because of his mother who was half Italian). This stunning work is one of Marx's most delightful declarations of love to Italy and its beauty.

Walter Gieseking performed the premiere of this virtuoso concerto and also was the soloist in numerous later performances till the 1950s. Castelli Romani has besides been performed in the United States and in several European countries (among others in England for the BBC) at least till the late 1950s. The Austrian pianist Frieda Valenzi has given many performances of this work with various Austrian orchestras in the 1950s and 60s. Later, in 1978 and 1981, another Austrian pianist, Hans Petermandl, performed the work twice, while the German pianist Julius Bassler frequently performed its 3rd movement with several German radio orchestras from the end of the 1960s to the end of the 1970s. The most recent performance of "Castelli Romani" took place on March 28/29, 1982, in the Stefaniensaal of Graz (pianist Alexander Jenner and the Grazer Philharmonisches Orchester conducted by Peter Schrottner). The movements are:

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE number not available). A version for two pianos is also available.

NEWS: The two piano concerti "Romantisches Klavierkonzert" (Romantic Piano Concerto) and "Castelli Romani" were recorded by the Label ASV with the American virtuoso David Lively as Vol. 4 of the Complete Orchestral Music series. For further information please click here.

1941-42:

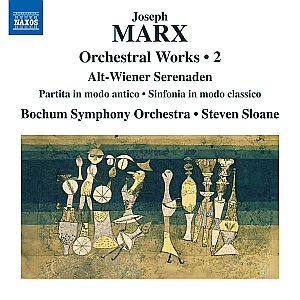

Alt-Wiener Serenaden (Old Vienna Serenades) for large orchestra. About 17-21 minutes. Dedicated to the Vienna Philharmonics on the occasion of their 100th anniversary. Composed within his tendency to classicism, in a style between Haydn and Schubert but it also includes Marx's characteristic elements of impressionism. Marx wrote it during his final work period in which he also composed his string quartets. The movements are:

Publisher: Universal Edition (UE 11358)

1944:

"Sinfonia in modo classico" for string orchestra. About 26 minutes. This is a string orchestra version of his own "Quartetto in modo classico" (not yet recorded in this string orchestra version). Publisher: Doblinger, Vienna. Score available. The movements are:

1945:

"Partita in modo antico" for string orchestra. About 26 minutes. This is a string orchestra version of his own "Quartetto in modo antico" (not yet recorded in this string orchestra version). Publisher: Doblinger, Vienna. Score available. The movements are:

NEWS: The above three orchestral works in traditional style were recorded as Volume 3 of the series (ASV). For further information please click here.

1946:

"Feste im Herbst" (also known as "Herbstfeier"; "Autumnal Revelries") for large orchestra. About 25 minutes. Is practically identical with the final movement of the Herbstsymphonie (for details see "Latest news" above where also an analysis of this work is given). Marx published this work in 1946 obviously as a reaction to the sad fact that the Herbstsymphonie hadn't been performed again over the last 10-15 years (the first three movements of the symphony even hadn't been performed for 20 years). The score is available at Universal Edition but one should note that this work is almost identical with the final movement of the Herbstsymphonie that has never been completely performed since the 1920s. Hence, a world premiere recording of "Feste im Herbst" should by all means bring on a first recording of the whole symphony.

Joseph Marx at his home in Vienna, Traungasse 6

(1963).

For more photos of this house please click here

Back to the overview of this chapter

Back to the overview of this chapter

Symphony No. 1 (1901)

Symphony No. 2 (1906)

My knowledge of these two symphonies is based on a letter written by Marx after the premiere of the Herbstsymphonie. There he wrote: "In fact, this symphony is my third symphony since I always kept secret my first symphony that I composed at the age of 19 and also my second one that I wrote at the age of 24." Due to the Liess biography one of these youth symphonies is in C sharp minor (I couldn't figure out which one, likely No. 2). Fact is that Marx reused themes of the adagio part/movement of the C sharp minor symphony later in his Herbstsymphonie.

One of the two youth symphonies is known as "Symphony in one movement for orchestra" and due to the Austrian National Library it has indeed an adagio part. These youth symphonies have never been published as Universal Edition doesn't have their scores. However, the score (a rough draft of 11 pages) of the unfinished "Symphony in one movement for orchestra" (that might be identical with the "Symphony in C sharp minor" that is mentioned in the Liess biography since they both include an adagio part) can be found at the Austrian National Library. Due to the first page of the score this symphony is Marx's 4th work (it's titled "opus 4" although Marx didn't use opus numbers. Perhaps Marx used opus numbers only for his earliest works and then gave up numbering after he had begun to compose his first huge series of Lieder.)

Piano Concerto. The score (a rough draft of 13 pages) can be found at the Austrian National Library. One might assume that this is the rough draft of his first piano concerto, the Romantisches Klavierkonzert that was written in 1919.

Fragmentary rough draft of a work for string orchestra (4 pages, Austrian National Library). No more information available.

Unidentified stage play, obviously never continued nor finished: On 4 Apr 1926 a journalist asked Marx about his current composing projects. Marx answered: "At the moment I am composing the Nordic Rhapsody and a stage play that is not an opera." Unfortunately I couldn't find out which work Marx was referring to. None of the rough drafts of Marx's orchestral works at the Austrian National Library can be connected with that obscure stage play.

Rough draft for a fanfare music (10 pages; Austrian National Library).

"Island-Suite" (1927-28, "Iceland Suite"). The unfinished score (a rough draft of 34 pages) of this work can only be found at Austrian National Library. In order to find out if "Island-Suite" is the rough draft of Marx's next work "Nordlands-Rhapsodie" one would have to compare the two scores. However, the fact that the "Nordlands-Rhapsodie" is based on the novel "Iceland Fisher" by Pierre Loti might be an indication of this assumption.

"Symphonische Rhapsodie" (Symphonic Rhapsody) for large orchestra (1929). About 9 minutes. This work is identical with the 1st movement of the Nordlands-Rhapsodie (see above). It was sometimes performed separately.

"Symphonische Tänze" (Symphonic Dances) for large orchestra. About 9 minutes. It seems to be a short version or a kind of variation on several themes from "Feste im Herbst" (see above; also see "Latest news" above) or a variation on themes that are directly taken from the "Herbstpoem" (final movement of the Herbstsymphonie). None of the sources has the score of this work of which I have an old recording. I guess that the score got lost after the work was performed and recorded by the Austrian radio station. Performance details due to the announcement at the beginning of my recording: Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Karl Etti who was one of the main conductors of Marx's orchestral works besides Max Schönherr and Karl Böhm.

Back to the overview of this chapter

Back to the overview of this chapter

Works for voice and orchestra:

Since Universal Edition was unable to provide a list of all "official" English titles (esp. regarding Marx's vocal works that were mainly translated by John Bernhoff), the English titles shown below were translated by myself and are therefore supplied without liability for errors.

(The scores of the following works for voice and orchestra/chamber ensemble can all be obtained at Universal Edition. The English lyrics are also available at UE for most of these works.)

NEWS: The works for voice and orchestra were recorded for ASV (as Vol. 2 of the CD series) with the soloists Angela Maria Blasi (soprano) and Stella Doufexis (mezzo-soprano). For more information please click here.

"Verklärtes Jahr" (Transfigured Year) -

A song cycle for medium voice and orchestra (1930-32). About

18-21 minutes. This is the last work of Marx's main "orchestral

period" (1919-1932). Its version for voice and piano has already

been commercially recorded by FY Solstice (see "Discography") but

one can hear an enormous difference between the sound worlds

created by these two different versions. This orchestral Song

Symphony is one of the most evident proofs for the fact that

Marx had never been able to realise his complex ideas before in his

works for voice and piano although the phenomenal pianistic

virtuosity of their piano parts creates a huge variety of

impressionistic effects that we won't hear in the piano parts of

songs written by any other Lied composer. Some critics even wrote

that Marx's songs for voice and piano were nothing but "Piano

concertos with voice obligato".

"Verklärtes Jahr" in its miraculous

orchestral version brings together a number of the greatest "sound

effects" that Marx has ever composed. Its five movements are:

Marx with some of his renowned Turkish students (Vienna, 1931):

Necil Kazim Akses (left), Marx, Cemal Resit Rey and Hasan Ferit Alnar

Orchestral scores of some of the following Orchestral Songs

were used as film music in the movie "Cordula" (1950). More information and

pictures of this movies's cinema magazine

can be found here

Marx orchestrated most of the following songs in the 1930s.

"Am Brunnen" (At the Fountain) for medium voice and string orchestra (1912). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Barcarole" for high voice and orchestra (1910). About 6 minutes. Lyrics by A. F. von Schack.

"Begegnung" (The Encounter) for medium voice and string orchestra (1912). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Der bescheidene Schäfer" (The unassuming Shepherd) for high voice and string orchestra (1910). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Christian Weisse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Der (Die) Liebste spricht" (The Darling is speaking) for medium voice and string orchestra (1912). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Erinnerung" (Memory) for medium voice and orchestra (1911). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Joseph von Eichendorff.

"Hat Dich die Liebe berührt" (If love hath entered thy heart) for high or low voice and orchestra (1908). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Paul Heyse.

"Japanisches Regenlied" (Japanese Rain Song) for medium voice and orchestra (1909). About 2 minutes.

"Jugend und Alter" (Youth and Age) for medium voice and orchestra (1909). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Walt Whitman.

"Maienblüten" (May Blossoms) for high voice and orchestra (1909). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Ludwig Jacobowsky.

"Marienlied" (Song of Mary) for high voice and orchestra (1910). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Novalis.

"Piemontesisches Volkslied" (Piemontesian Folk Song) for high voice and string orchestra (1911). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Max Geissler. Also available in a version for high voice and string quartet.

"Selige Nacht" (Blessed Night) for high voice and orchestra (1913/14). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Otto Erich Hartleben.

"Sendung" (The Message) for medium voice and string orchestra (1912). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Sommerlied" (Summer Song) for high voice and orchestra (1909). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Emmanuel Geibel.

"Ständchen" (Serenade) for high voice and string orchestra (1912). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for high voice and string quartet.

"Und gestern hat er mir Rosen gebracht" (He brought me roses yesterday) for high voice and orchestra (1908). About 2 minutes. Lyrics by Th. Lingen.

"Venetianisches Wiegenlied" (Venetian Lullaby "Nina Ninana") for medium voice and orchestra (1912). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available "Venetianisches Wiegenlied" for medium voice and string orchestra with harp. Additionally available in a version for medium voice and string quartet with harp. At the Austrian National Library besides available in a version for for voice and string quartet.

"Waldseligkeit" (Bliss in the Woods) for high voice and string orchestra (1911). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Richard Dehmel. Also available in a version for high voice and string quartet.

"Wofür" (For what) for medium voice and string orchestra (1912). About 1 minute. Lyrics by Paul Heyse. Also available in a version for voice and string quartet.

"Zigeuner" (Gipsy) for high voice and orchestra (1911). About 3 minutes. Lyrics by Max Geissler.

Besides, Marx arranged five songs by Hugo Wolf for voice and orchestra:

Back to the overview of this chapter

Back to the overview of this chapter

Choral works with/without orchestra:

(Scores are available at UE. Not yet recorded.)

|

My following article was issued in the monthly newsletter of European Cultural Services (Editor: Heinz Prammer, Vienna) that is sent to thousands of choral societies in Europe. Click here to visit the website of European Cultural Services. Renaissance of Joseph Marx's outstanding choral worksWritten in German and translated to the English

|

Works for mixed chorus:

"Herbstchor an Pan" (Autumn Chorus to Pan)

for mixed choir, boys' choir, orchestra and organ (1911).

About 20 minutes, lyrics by Rudolf Hans Bartsch. The subtitle of

this symphonic poem is: "In memory of a luminous autumn day

in the South Steiermark". Due to Liess's biography this

work creates a glimmering world of impressionism and makes

intensive use of the art of counterpoint. With its powerful

sonority and effective polyphony this treasure is said to be the

precursor of the Herbstsymphonie. Furthermore, Marx

here reuses elements of the main theme of "Windräder"

(Wind Mills) that is said to be his most brilliant song at

all. No performance dates available at all. Seemingly never been

performed again since its year of origin. DECEMBER 2001: As reported by Dr. Roman

Rocek from the Austrian Richard Maux Society, there has been a

performance of "Herbstchor an Pan" in the 1950s in the

Musikverein. [Note: Richard Maux, 1893-1971, a vastly neglected

Austrian late romantic who was friends with Marx and composed in a

similar style.] Due to the piano scores of "Herbstchor an Pan" and

"Morgengesang", Marx's charmingly romantic impressionism was here

developed to its utmost level only surpassed later in his

Herbstsymphonie. I hereby call upon all choirs to cooperate

with their orchestras in order to perform or record these two

masterworks of romantic choral music.

About 20 minutes, lyrics by Rudolf Hans Bartsch. The subtitle of

this symphonic poem is: "In memory of a luminous autumn day

in the South Steiermark". Due to Liess's biography this

work creates a glimmering world of impressionism and makes

intensive use of the art of counterpoint. With its powerful

sonority and effective polyphony this treasure is said to be the

precursor of the Herbstsymphonie. Furthermore, Marx

here reuses elements of the main theme of "Windräder"

(Wind Mills) that is said to be his most brilliant song at

all. No performance dates available at all. Seemingly never been

performed again since its year of origin. DECEMBER 2001: As reported by Dr. Roman

Rocek from the Austrian Richard Maux Society, there has been a

performance of "Herbstchor an Pan" in the 1950s in the

Musikverein. [Note: Richard Maux, 1893-1971, a vastly neglected

Austrian late romantic who was friends with Marx and composed in a

similar style.] Due to the piano scores of "Herbstchor an Pan" and

"Morgengesang", Marx's charmingly romantic impressionism was here

developed to its utmost level only surpassed later in his

Herbstsymphonie. I hereby call upon all choirs to cooperate

with their orchestras in order to perform or record these two

masterworks of romantic choral music.

"Ein Neujahrshymnus" (A New Year's Hymn) for mixed choir and orchestra (1914). In Autumn 2004, this work was orchestrated by Stefan Esser and Berkant Haydin (author of this website; see red info box below). Text: Joseph Marx. Duration: approx. 10 minutes. A majestic, stirring hymn to life. Due to the highly inspired text of Joseph Marx, this work can also be performed as a sacred work. Film music composers arranged fragments of it for mixed choir and orchestra in the year 1950.

"Berghymne" (Mountain Hymn) for mixed choir and orchestra (possibly written in 1910). Text: Alfred Fritsch. Duration: approx. 4 minutes. The original score of this dazzling rarity is available as a "particell" (reduced score) i.e. a kind of extended piano score including choral voices (unison) and a few basic orchestral voices. It was fully arranged by Stefan Esser and Berkant Haydin for mixed choir and orchestra in 2005.

|

"A New Year's Hymn" and "Mountain Hymn" by Joseph Marx Orchestrated by Stefan Esser and Berkant Haydin (the author of this website)! * * * published by Universal Edition * * * Click here for detailed info, music samples (MP3) and score pages |

Works for male chorus:

"Morgengesang" (Morning Chant) for male choir and orchestra (1910; orch. 1934 by A. Wassermann). About 8 minutes, lyrics by Ernst Decsey. Also available in a version for male choir, brass instruments and organ, and besides in another version for male choir and brass orchestra. "Morgengesang" was originally written for male choir and orchestra in 1910. In the summer of 1932, Marx arranged it for brass orchestra on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Goethe's death. The latest performances of which I know have been in 1947 (Wiener Schubertbund and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Prof. Viktor Keldorfer) and in 1951 (in Switzerland), and also by the Wiener Schubertbund in 1954 (with organ), in 1956 performed by the Niederösterreichisches Tonkünstlerorchester conducted by Leo Lehner and in 1969 conducted by Heinrich Gattermeyer (without orchestra).